canto a mí mismo (7ª parte)

No soy un mundo ni un complemento de un mundo,

Soy el camarada y compañero de los demás, todos exactamente tan inmortales e insondables como yo;

Ellos no saben cómo de inmortales, pero yo lo sé.

Cada naturaleza por si misma también es la suya propia. . . . para mi, míos el hombre y la mujer.

Para mi, todos lo que han sido niños y los que aman a las mujeres

Para mi, el hombre que es orgulloso y siente cómo le molesta ser menospreciado

Para mi el encanto y la solterona. . . . para mi las madres y las madres de sus madres,

Para mi los labios que han sonreído, los ojos que han derramado lágrimas,

Para mi los niños y los padres de los niños.

¿Quién necesita estar temeroso de la mezcla?

Descúbrete. . . . no eres culpable para mi, ni rancio, ni rechazado,

Veo a través del velo y la zaraza lo quieras o no,

Y estoy alrededor, tenaz, codicioso, incansable. . . . y nunca puedo ser sacudido lejos.

El pequeño duerme en su cuna,

levanto la gasa y lo contemplo un rato y silenciosamente quito las moscas con mi mano.

El joven y la ruborizada chica suben a un lado de la tupida colina.

Entrecerrando los ojos los miro desde lo alto.

El suicidio se extiende sobre el sangriento suelo de la habitación

es así . . . . Soy testigo del cadáver . . . . allí la pistola había caído.

El cotilleo del pavimento . . . . las ruedas de los carros y el lodo de las suelas de las botas, el hablar

de los transeúntes.

El pesado omnibus, el conductor con su interrogatorio pulgar, el ruido de los herrados caballos

sobre el suelo de granito.

El carnaval de trineos, el tintineo y los estridentes chistes y las pieles de las bolas de nieve;

Los hurras para los favoritos mas populares. . . . la furia de las despiertas multitudes,

el aleteo del cortinaje de las camillas – el enfermo dentro, sujeto hacia el hospital.

La reunión de enemigos, el repentino juramento, los golpes y caídas.

El emocionado gentío — El policía con su estrella rápidamente haciendo su pasillo hacia el centro del gentío;

las impasibles piedras que reciben y devuelven tantos ecos.

Las almas avanzando. . . . ¿ Son ellas invisibles mientras que el más mínimo átomo de las piedras es visible ?

Los que gimen por sobrealimentados o los mediomuertos de hambre que caen sobre las banderas,

con insolación o e un arrebato.

Cuántas exclamaciones repentinas de mujeres que van a casa y dan a luz a sus bebés,

Qué vivo y escondido lenguaje está siempre vibrando aquí. . . . Cuánto grito prudente por decoro.

Las detenciones de delincuentes, humillaciones, las adúlteras que hacen ofertas, las aceptaciones,

los rechazos de labios convexos,

me preocupan, o la resonancia de ellos. . . . vuelvo una y otra vez.

Las grandes puertas del granero en el campo están abiertas y listas

La hierba seca de la época de cosecha llenará la lenta y alargada carreta,

La clara luz del día juega con el marrón grisáceo y el entreteñido verde,

Los montones son embalados en el combado altillo del granero;

Estoy allí . . . . ayudo . . . . vuelvo, estirado encima de la carga,

Siento sus suaves sacudidas. . . . una pierna reclinada sobre la otra,

Salto desde los travesaños y aprovecho el trébol y el timoteo,

Y ruedo patas arriba y se enreda mi pelo lleno de briznas.

Solo, lejos en el bosque y las montañas, cazo,

Vagando sorprendido de mi propia agilidad y gozo,

Al final de la tarde elijo un lugar seguro para pasar la noche,

encendiendo un fuego y haciendo a la brasa la presa recién muerta,

Quedándome dormido profundamente sobre el montón de hojas, mi perro y el arma, a mi lado.

El velero Yankee está bajo sus tres izadas velas. . . . ellas cortan las brillantes y rápidas nubes

Mis ojos se posan en la tierra . . . . trazo una curva hacia su proa, mejor dicho, grito jubiloso desde la cubierta.

Los barqueros y buscadores de almejas se levantaron pronto y se detuvieron por mi.

Metí el final de mis pantalones en las botas y fuimos y lo pasamos bien.

Tendrías que haber estado con nosotros ese día, alrededor del caldero de sopa de pescado.

Vi el matrimonio del trampero al aire libre, en el lejano oeste….la novia era una chica pelirroja,

Su padre y sus amigos sentados cerca con las piernas cruzadas, fumando sin hablar…. tenían mocasines

en sus piesy largas mantas gruesas colgando de sus hombros;

El trampero estaba tumbado en un banco…. estaba vestido con la mayor parte de sus pieles….

Su exhuberante barba y rizos, protegían su cuello.

Una mano descansaba sobre su rifle …. La otra mano agarraba firmemente la muñeca de la chica pelirroja.

Ella tenía largas pestañas …. Su cabeza estaba al descubierto …. sus gruesos y lacios mechones

descendían sobre sus voluptuosas piernas y alcanzaban hasta sus pies.

nuestras versiones

[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]

song of myself

I am not an earth nor an adjunct of an earth,

I am the mate and companion of people, all just as immortal and fathomless as myself;

They do not know how immortal, but I know.

Every kind for itself and its own . . . . for me mine male and female,

For me all that have been boys and that love women,

For me the man that is proud and feels how it stings to be slighted,

For me the sweetheart and the old maid . . . . for me mothers and the mothers of mothers,

For me lips that have smiled, eyes that have shed tears,

For me children and the begetters of children.

Who need be afraid of the merge?

Undrape . . . . you are not guilty to me, nor stale nor discarded,

I see through the broadcloth and gingham whether or no,

And am around, tenacious, acquisitive, tireless . . . . and can never be shaken away.

The little one sleeps in its cradle,

I lift the gauze and look a long time, and silently brush away flies with my hand.

The youngster and the redfaced girl turn aside up the bushy hill,

I peeringly view them from the top.

The suicide sprawls on the bloody floor of the bedroom.

It is so . . . . I witnessed the corpse . . . . there the pistol had fallen.

The blab of the pave . . . . the tires of carts and sluff of bootsoles and talk of the promenaders,

The heavy omnibus, the driver with his interrogating thumb, the clank of the shod horses on the granite floor,

The carnival of sleighs, the clinking and shouted jokes and pelts of snowballs;

The hurrahs for popular favorites . . . . the fury of roused mobs,

The flap of the curtained litter — the sick man inside, borne to the hospital,

The meeting of enemies, the sudden oath, the blows and fall,

The excited crowd — the policeman with his star quickly working his passage to the centre of the crowd;

The impassive stones that receive and return so many echoes,

The souls moving along . . . . are they invisible while the least atom of the stones is visible?

What groans of overfed or half-starved who fall on the flags sunstruck or in fits,

What exclamations of women taken suddenly, who hurry home and give birth to babes,

What living and buried speech is always vibrating here . . . . what howls restrained by decorum,

Arrests of criminals, slights, adulterous offers made, acceptances, rejections with convex lips,

I mind them or the resonance of them . . . . I come again and again.

The big doors of the country-barn stand open and ready

The dried grass of the harvest-time loads the slow-drawn wagon,

The clear light plays on the brown gray and green intertinged,

The armfuls are packed to the sagging mow:

I am there . . . . I help . . . . I came stretched atop of the load,

I felt its soft jolts . . . . one leg reclined on the other,

I jump from the crossbeams, and seize the clover and timothy,

And roll head over heels, and tangle my hair full of wisps.

Alone far in the wilds and mountains I hunt,

Wandering amazed at my own lightness and glee,

In the late afternoon choosing a safe spot to pass the night,

Kindling a fire and broiling the freshkilled game,

Soundly falling asleep on the gathered leaves, my dog and gun by my side

The Yankee clipper is under her three skysails . . . . she cuts the sparkle and scud,

My eyes settle the land . . . . I bend at her prow or shout joyously from the deck.

The boatmen and clamdiggers arose early and stopped for me,

I tucked my trowser-ends in my boots and went and had a good time,

You should have been with us that day round the chowder-kettle.

I saw the marriage of the trapper in the open air in the far-west . . . . the bride was a red girl,

Her father and his friends sat near by crosslegged and dumbly smoking . . . . they had moccasins to their feet

and large thick blankets hanging from their shoulders;

On a bank lounged the trapper . . . . he was dressed mostly in skins . . . . his luxuriant beard and curls

protected his neck,

One hand rested on his rifle . . . . the other hand held firmly the wrist of the red girl,

She had long eyelashes . . . . her head was bare . . . . her coarse straight locks descended upon

her voluptuous limbs and reached to her feet.

[/ezcol_1half_end]

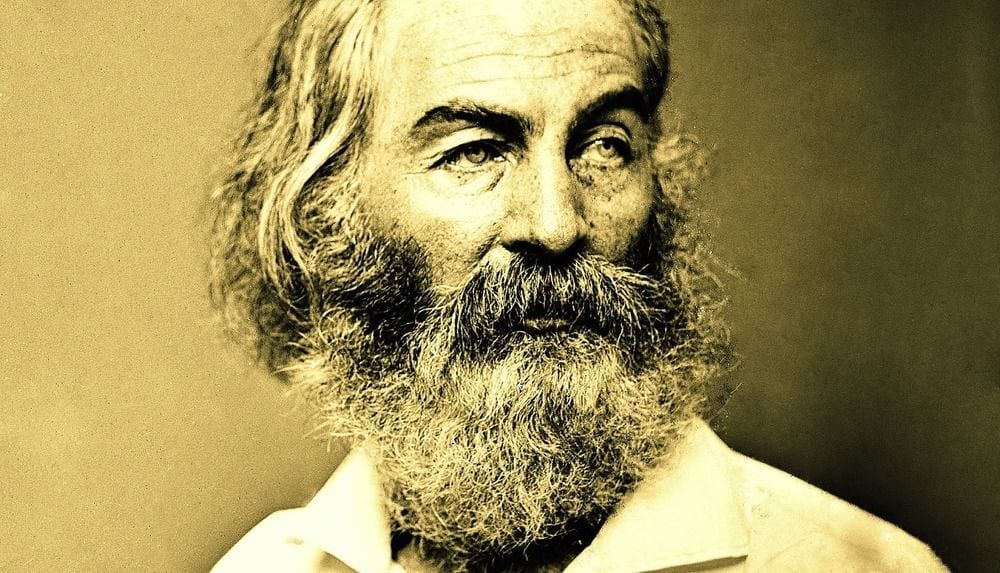

Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892. Leaves of Grass (1855)

Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library

Bueno, Whitman es… magnánimo, lo que incluye, supongo,

un optimismo casi insultante: todo es fácil, o puede serlo; todo

puede ser solución y respuesta. Así da gusto.

Gracias

Narciso